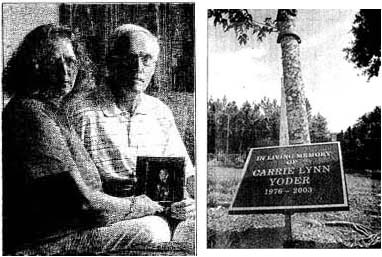

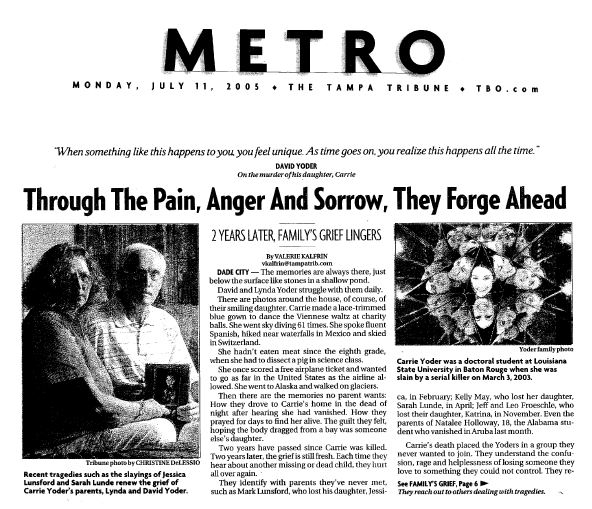

Tribune photos by Christine DeLessio

By Valerie Kalfrin

The Tampa Tribune, July 11, 2005

2006 Florida Press Club Award Winner: Excellence in Crime Reporting

DADE CITY — The memories are always there, just below the surface like stones in a shallow pond.

David and Lynda Yoder struggle with them daily.

There are photos around the house, of course, of their smiling daughter. Carrie made a lace-trimmed blue gown to dance the Viennese waltz at charity balls. She went sky diving 61 times. She spoke fluent Spanish, hiked near waterfalls in Mexico and skied in Switzerland.

She hadn’t eaten meat since the eighth grade, when she had to dissect a pig in science class.

She once scored a free airplane ticket and wanted to go as far in the United States as the airline allowed. She went to Alaska and walked on glaciers.

Then there are the memories no parent wants: How they drove to Carrie’s home in the dead of night after hearing she had vanished. How they prayed for days to find her alive. The guilt they felt, hoping the body dragged from a bay was someone else’s daughter.

Two years have passed since Carrie was killed. Two years later, the grief is still fresh. Each time they hear about another missing or dead child, they hurt all over again.

They identify with parents they’ve never met, such as Mark Lunsford, who lost his daughter, Jessica, in February; Kelly May, who lost her daughter, Sarah Lunde, in April; Jeff and Leo Froeschle, who lost their daughter, Katrina, in November. Even the parents of Natalee Holloway, 18, the Alabama student who vanished in Aruba last month.

Carrie’s death placed the Yoders in a group they never wanted to join. They understand the confusion, rage and helplessness of losing someone they love to something they could not control. They remember throngs of reporters, phone calls and visits from friends, and the awful vacuum when the attention fades and all that’s left is silence.

People on the outside talk of closure. The Yoders know that doesn’t happen.

“When something like this happens to you, you feel unique,” David Yoder said. “As time goes on, you realize this happens all the time.”

His wife sometimes reaches out to victims’ families, offering her phone number in case they want to talk. She doesn’t expect them to call right away. Perhaps they never will.

“Somehow you survive it,” she said, “but you don’t come through it the same person.”

As published in The Tampa Tribune

‘All Those Losses’

Carrie was 26 when she died. Her parents last saw her alive at Christmas in 2002. She gave them a book, “Earth from Above,” showing aerial photos of places around the world: markets and playgrounds, ice floes and olive plantations.

Carrie worked as a botanist; not work, really, because she loved nature. She had driven to her parents’ home in Lake Jovita from Baton Rouge, La. She was earning her doctorate at Louisiana State University, studying coastal wetlands.

She left before New Year’s Eve. She planned to spend a few days in Chipley with her boyfriend’s family.

“Her dad was scraping the frost off her windshield, and she was making ‘snowballs’ and throwing them at me because I wasn’t helping,” Lynda Yoder said.

Their exuberant daughter — the people magnet, the adventurer — died about two months later, on March 3, 2003, at the hands of a serial killer.

The DNA of Derrick Todd Lee, 36, a truck driver convicted in October, linked him to the deaths of Carrie and six other women. One was a Marine fluent in six languages. One owned an antiques business. One was a nurse. Two, like Carrie, attended LSU. Another had a young son; her body was never found.

The oldest was 44. The youngest, 19. They were bright women, role models, Lynda Yoder said. “All those losses.”

When Carrie’s younger brother, Greg, gets married someday, Carrie won’t be there. Her father, who was reluctant to give her away as a bride, can’t attend friends’ weddings anymore. They remind him of what he will never do.

David Yoder, 60, retired as a systems analyst for IBM last year. With more time to himself, it’s harder for him to escape the memories, he said.

His daughter’s death has made him angry, bitter, “disgusted with the whole system,” he said. Lee had an extensive criminal history, including charges of domestic abuse and attempted first-degree murder. “lt’s just incredible that animals like this are walking around.”

His wife thinks “anger can eat you up.” She tries to channel it in a positive way, like raising money for scholarships in Carrie’s memory at LSU and the University of Florida.

Hopes And Dreams Die

Lynda Yoder has become an advocate, like other mothers of Lee’s victims, for expanding the scope of the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System Program, or CODIS. They want CODIS to include DNA for anyone arrested for sexual abuse or domestic violence. If Lee’s DNA had been there, Lynda said, perhaps investigators could have found him sooner and spared some of their daughters.

She likes to stay busy. “Downtime is too much time to think,” said Lynda, 58. “Too much time to realize what’s not there.”

Her daughter’s death has made her more emotional, she said. She cries more easily.

“I vowed not to let Derrick Todd Lee kill me too, but he has killed my hopes and dreams for happiness,” she said. “It is a daily struggle that I hope to survive.”

Carrie’s presence covers her parents’ home. Her collection of frog figurines adorns one bookcase in the living room. Photos of her abound.

Lynda flips through one of Carrie’s journals sometimes to see her daughter’s handwriting. She can’t bring herself to read it.

Before Carrie disappeared, Lynda planned a trip to Baton Rouge that March, during spring break at Brewster Technical Center in Tampa, where Lynda teaches. They planned a mother-daughter week full of sightseeing, movies, shopping and Louisiana cuisine. Carrie wanted to tour local plantations and go bird-watching. She wanted to drive her mother to New Orleans to dine.

Instead, that week Lynda and David returned home with Carrie’s belongings. They wondered what to do with it all, what to keep.

“The littlest thing triggers you,” Lynda said. “I found this trinket box with frogs on the lid, and I started crying in the store because I would’ve bought it for her. I wound up buying it for me.”

That Last Day

On March 2, 2003, the day before she died, Carrie went to Mardi Gras. Her mother has a photo of her there, wearing a light-blue sweater, jeans and necklaces of plastic beads.

She was home on her computer at 7:45 p.m. the next day, police learned from the computer’s clock. Lee surprised her and spirited her away. To this day, her parents don’t know how.

Carrie’s boyfriend reported her missing on March 5, after Carrie hadn’t returned his phone calls. Lynda and David drove to Baton Rouge. They met members of a law enforcement task force investigating the deaths of three other women. They also met the women’s mothers.

“We said, ‘We don’t want to join your club. We want Carrie found with her heart still beating,’” Lynda remembered.

But on March 13, 2003, a fisherman found Carrie’s body in Louisiana’s Whiskey Bay. She had been raped, beaten and strangled. Her spleen and liver were punctured. She had seven broken ribs.

“We were lucky we found her,’’ Lynda said. ·

She absorbed details of evidence from Carrie’s house, such as a drop of Carrie’s blood on her purse. Was Carrie unconscious when Lee took her away?

“You try to get these little scenarios in your mind, and then you think, ‘I can’t go there,’“ Lynda said.

The questions don’t subside. She and her husband are haunted by what they don’t want to know: how their daughter spent her last moments.

‘‘What were her thoughts? Who was she thinking of? Did she try to defend herself?” Lynda said. “And how awful that must be, knowing you’re going to be dead.”

In August 2004, Lee was convicted of second-degree murder in the death of Geralyn DeSoto, 21, who registered for graduate school at LSU. He was sentenced to life at the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola.

He was convicted in October of the murder of another LSU graduate student, Charlotte Murray Pace. Lynda attended the 17-day trial. David couldn’t. “I didn’t want to be there,” he said.

The prosecution was allowed to present evidence about all the women’s deaths. When they showed pictures of Carrie’s body, Lynda, who is nearsighted, took off her glasses. “I don’t want to see my daughter like that,” she said.

In December, Lee received a death sentence. That was enough, Lynda said. The families couldn’t endure more trials.

In Such Pain, Every Day

Now, the Yoders wrestle with their own purgatory: life without Carrie.

When Lynda read about Katrina Froeschle, the 25-year-old insurance adjuster who was killed on the job in November, she called a Tribune reporter to offer her phone number to Froeschle’s parents. “I know what they’re going through,” she said.

In April, she read about Sarah Lunde, 13, of Ruskin, who police later would say was killed by her mother’s former boyfriend. When Sarah was missing, Lynda saw Sarah’s mother, Kelly May, photographed before a cluster of microphones, appealing for Sarah’s safe return. With her was Mark Lunsford, father of the 9-year-old Homosassa girl who police said was raped and killed by a convicted sex offender.

“He hates to be there,” Lynda said at the time, pointing at the picture, “but he has to be.”

Recently, David and Lynda wanted to watch a recent News Channel 8 interview with Mark Lunsford. When he said he tries to stay busy so he doesn’t think of his daughter, Lynda murmured in agreement. Another story during the broadcast outlined possible legal problems with the confession of Jessica’s accused killer. David grumbled, repulsed.

They know Carrie would not want for them to be in such pain over missing her, but they are. Every day.

Lynda e-mails the mothers of Lee’s other victims — her extended family — when memories overwhelm her. Each year, the Yoders and their friends light a candle at 7:45 p.m. on March 3, the last time they know Carrie was alive.

On her birthday, Nov. 6, they do nothing but “get through the day,” Lynda said.

They have not yet held a final memorial service for Carrie, who was cremated. They have permission to scatter her remains along Weeks Bay in Alabama, where she did research for her doctorate. A boardwalk there will be dedicated to Carrie after she posthumously receives her degree in December.

December — forever now the month they last saw Carrie, that Christmas before she died. Last year, the Yoders spent Christmas in New Orleans, for something different.

It snowed.