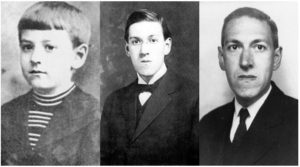

H.P. Lovecraft L to R in 1900, 1915, 1934 / CC/Wikipedia

By Valerie Kalfrin

Signature Reads, Nov. 4, 2016

Author Neil Gaiman, a longtime fan of horror writer H.P. Lovecraft, jokes that the typical Lovecraftian tale has someone going insane and continuing to write while an unspeakable, tentacled beast creeps up from the depths to ensnare him during his final moments. Yet like that stealthy creature, the reach of this forerunner of speculative fiction continues to expand, touching storytellers in literature, film, TV, and video games.

This year alone, Kij Johnson’s new novella, The Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe, published by Tor, follows a woman on a quest through a fantasy landscape with images out of Lovecraft’s short story, The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath. Ron Perlman, Christopher Plummer, and Jane Curtin lend their voices to the animated film Howard Lovecraft & the Frozen Kingdom, which debuted in Canada in October 2016. In the film, a teen Lovecraft accidentally unleashes trouble through the Necronomicon. That book of dark magic – one of the author’s best-known creations – is the same cause of havoc in Sam Raimi’s comedic “Evil Dead” series, most recently in “Ash vs Evil Dead,” now airing on Starz. Meanwhile, other Lovecraft-inspired stories are in the works around the world, such as “Arkham Sanitarium,” a UK anthology film of three of Lovecraft’s stories.

Seventy-nine years after his death – he died penniless at forty-six years old – Lovecraft is still in style.

“Lovecraft … opened the way for me, as he had done for others before me,” notes author Stephen King, who like Gaiman and director Guillermo del Toro was enthralled as a youth by Lovecraft’s imaginings. “[I]t is his shadow, so long and gaunt, and his eyes, so dark and puritanical, which overlie almost all of the important horror fiction that has come since.”

Born in Providence, Rhode Island, Howard Phillips Lovecraft was a sickly child around the turn of the twentieth century whose adult success as a writer was limited to stories published in pulp magazines such as Weird Tales and Astounding Stories. He’s perhaps best known for the “Cthulhu mythos,” stories centered around an extraterrestrial race of godlike beings who still lurk on Earth, ready to reemerge.

“We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far,” Lovecraft wrote in 1928’s The Call of Cthulhu, where he also writes: “I have looked upon all the universe has to hold of horror, and even the skies of spring and flowers of summer must ever afterward be poison to me.”

With his first-person narrators, heavy exposition, and repetitive style, Lovecraft can strike some readers as amateurish, and has been criticized for his overt racism. The World Fantasy Awards recently decided to change the design of its trophy, bearing Lovecraft’s likeness, over controversy about his bigotry, The Irish Times reported.

Yet those who recognize his influence say his continued resonance lies in his fantastical ideas – inspired by Darwinian evolution and Einsteinian physics – that placed humans at a rather meager place in the universe.

“What most people are fans of is not Lovecraft, but Lovecraft’s ideas,” John Brownlee wrote in Wired, paraphrasing Gaiman, “his vision of humanity being weak and helpless and surrounded by malevolent cosmic evil. Yes, there are gods. We are not alone in the universe. But our gods hate us.”

Joyce Carol Oates, writing in The New York Review of Books in 1996, notes that Lovecraft’s fiction, “set in meticulously described, historically grounded places,” often involves a curious male protagonist who “pursues a mystery it would be wiser for him to flee.”

The resulting reveal is a bleak, cerebral horror that gets under our skin more than a visceral one does. “There is a melancholy, operatic grandeur in Lovecraft’s most passionate work, like The Outsider and At the Mountains of Madness; a curious elegiac poetry of unspeakable loss, of adolescent despair, and an existential loneliness so pervasive that it lingers in the reader’s memory, like a dream, long after the rudiments of Lovecraftian plot have faded,” Oates writes.

This fatalistic view taps a cultural nerve, scholars say, with otherworldly beings such as the octopus/dragon/human caricature Cthulhu and Yog-Sothoth acting as “avatars for the impersonal forces of the universe in all of their capriciousness, power, and inevitable triumph.”

Humans never stop questioning our place in the universe or seeking meaning in our lives. So authors like Lovecraft become the cynical counterpart to the hopeful perspective of authors such as J.R.R. Tolkien, notes scholar and author Amy H. Sturgis.

“In the midst of societal upheaval and political and economic strife, what, if anything, is solid ground, unchanging, larger than the self? Where do we belong as individuals, or as members of a community? And what are we to make of the processes that seem to threaten the familiar, loved institutions of our civilization?” Sturgis writes. “As the twenty-first century unfolds as a time of rapid innovation, vast change, cultural conflict, violent warfare, and natural disasters, it is not difficult to see why these questions might be at the forefront of many readers’ minds.”