Difference Is In Reporting Methods

As published in The Tampa Tribune

By Valerie Kalfrin

The Tampa Tribune, Feb. 11, 2006

2006 Florida Press Club Award Winner: Excellence in Crime Reporting

TAMPA — Interpreting crime statistics can be a headscratching exercise. Imagine these scenarios:

- Two couples leave a restaurant after a late dinner. An armed man accosts them in the parking lot and takes the men’s wallets and the women’s purses. Four people are robbed, but in federal statistics, this is considered a single robbery.

- A stray bullet passes through a house, startling a woman and three children. In federal statistics, this counts as four aggravated assaults.

- At an apartment complex, a man shatters a bedroom window, climbs inside, beats a woman, then takes jewelry from her nightstand. Police write a report about the burglary, theft and beating, but for statistical purposes, report only the beating, an aggravated assault, to the FBI.

On Tuesday, Tampa Police Chief Stephen Hogue called a news conference with Mayor Pam Iorio to announce Uniform Crime Report statistics — a standardized system maintained by the FBI — showing that the city’s crime rate dropped 16.8 percent from 2004 to 2005.

But as the hypothetical examples above illustrate, these statistics do not give residents the full picture.

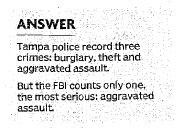

The Uniform Crime Report uses seven categories called Part I crimes to calculate local and national crime rates: murder and non-negligent manslaughter, forcible sex offenses, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny and motor-vehicle theft.

The Uniform Crime Report uses seven categories called Part I crimes to calculate local and national crime rates: murder and non-negligent manslaughter, forcible sex offenses, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny and motor-vehicle theft.

The system has meticulous and often baffling guidelines meant to eliminate differences among jurisdictions and ensure that incidents are counted once — except violent crimes with multiple victims. For instance, a dozen cars burglarized at an apartment complex overnight are considered one burglary, but a double homicide counts as two deaths.

“It’s not intended to give you a comprehensive view,” said Jacqueline Cohen of the National Consortium on Violence Research at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

Off By 3 Percent

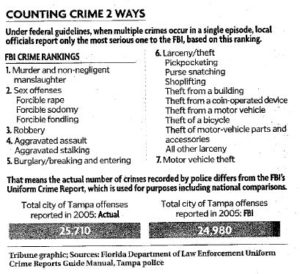

The Tampa Police Department is among about 17,000 law enforcement agencies nationwide that use Uniform Crime Reporting. Because of gaps in the UCR, and the need to track crimes by Florida statute, the department keeps two sets of crime statistics: actual crimes reported to police, and numbers adjusted for the federal government. Records clerks classify each incident for the FBI according to a manual provided by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement.

“We do what’s required by the federal government to keep a uniform system,” police spokeswoman Laura McElroy said.

Hogue on Tuesday said the department had reported “more crimes than we needed to” in previous years. Officials discovered in October 2004 that they were not using the FBI’s methodology and switched in 2005, he said.

The switch means the department’s actual overall figures differ from the overall Uniform Crime Report number by about 3 percent. Locally, “we are extremely thorough in our crime stats,” McElroy said. “If a crime occurs in the city of Tampa, it’s going to be reported in our system.”

It just might not be reported to the FBI. Tampa police recorded 13,775 larcenies in 2005, but they dropped to 12,564 once converted into the FBI’s statistics. Police statistics show 2,910 motor vehicles were stolen in Tampa last year, but the FBI shows 2,793.

Other categories grew in the FBI’s statistics. Tampa police recorded 266 forcible sex offenses in 2005, but the UCR shows 275. There were 4,811 burglaries in the police statistics last year, but 4,914 in the federal statistics.

Only the number of murders and non-negligent manslaughters stayed the same in both sets of figures: 22.

Only the number of murders and non-negligent manslaughters stayed the same in both sets of figures: 22.

Underreporting, Other Flaws

When more than one crime occurs in the same incident, police must pick one to report based on a hierarchy developed by the FBI. The further down the hierarchy, the more crimes drop out, Cohen said.

For instance, “you might not get all the rapes because the person was also murdered.”

The Uniform Crime Report system was developed in 1929. Its strength is its consistency, which allows authorities to compare trends over time, said Lorie Fridell, an associate professor of criminology at the University of South Florida.

But residents should be aware of its shortcomings. “The information they’re getting is going to be an underreporting of crime in their area,” she said.

The data can be flawed because of decisions made by those categorizing each incident or by policy changes, said Jim Lynch, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York. For instance, the New York Police Department in the budget-crunched 1970s stopped sending patrol cars to burglaries with losses of less than $10,000. New York police asked people to come in and file a complaint instead.

Some agencies have inflated numbers to get federal money. That happened during the 1990s, when community policing programs were funded based on crime reporting, Lynch said.

“People from small places … put in these earmarks to make the funds go where they weren’t needed,” he said.

Other agencies skew their numbers to look better. The Philadelphia police came under fire in the 1990s after an investigation discovered thousands of rapes went unreported by classifying them as “investigation of person.”

Whether the misreporting is deliberate or accidental, residents suffer, Lynch said. Police agencies collect a tremendous amount of data, but shoehorning it into the FBI format does not extrapolate crimes residents want to track, such as crimes in schools, he said.

“We need to get off our duff and design a better set of indicators to deal with the technology we have today.”

Alternate System Not Perfect

The FBI recognizes the Uniform Crime Report’s shortcomings. In its annual “Crime In the United States” report, the agency warned that the statistics are voluntarily supplied by law enforcement. How they are ranked is “merely a quick choice made by the data user; they provide no insight into the many variables that mold the crime in a particular town, city, county, state, or region,” the report said.

An alternative is the National Incident-Based Reporting System, which the FBI developed in the late 1980s. It collects data on 22 categories and records items such as victim, property and offender. It also has error checks to spot miscategorized data, said Don Faggiani, a law enforcement consultant who formerly worked for the Police Executive Research Forum in Washington.

He estimated that only about 5,200 departments nationwide use this system because it can be time-intensive and requires some change to record-keeping. No agency in Florida uses the system, which also is not perfect.

“There’s so much inconsistency in crime reporting in the United States that it’s really hard to tell what’s going on,” Faggiani said.